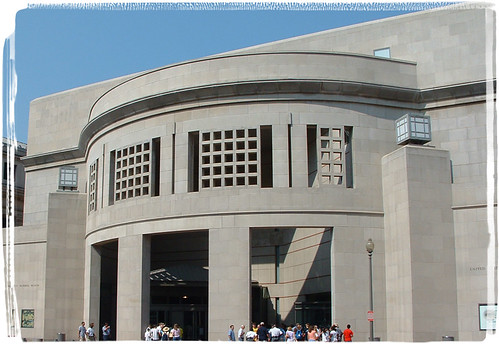

One of the things on our 'to do list' while in D.C. was to visit the

One of the things I am now interested in, is the use of texts within other texts, and what happens to those texts when they are reused in new contexts. In fact metalepsis is a term used to denote the intertextual use of one word, or trope, in a text to denote the entire context of a previous text. An example of this can be found inside the

context of a previous text. An example of this can be found inside the

You Are My Witnesses Isaiah 43.10

Hemmed in by the shadows of what appear to be prison bars. The metal and brick architecture reproduce the feeling of oppression and fear of the death camps. This is a text that obviously signifies on many different levels.

Firstly, it is meant to be an imperative to the visitors of the Holocaust museum. Their journey through the monument initiates them into the web of witnesses, and as such the onus is on them to witness to the world what they have seen, which implies that as witnesses they will never allow such atrocities to happen again.

Secondly, the context of Isaiah 43 speaks about the motifs of exile, restoration, exodus, and the servant. It is significant that this is a passage of extreme hope; it is a passage that speaks to those who are in exile, those who have every reason to be hopeless. But it speaks of hope in a profoundly new way, for this passage speaks of the occasion where YHWH has lost the last battle, the occasion where the Babylonian gods have defeated YHWH and proved themselves to be the more powerful gods. The proof of YHWH's loss is that his people have been taken captive, and are exiled.

Thirdly, when Isaiah 43 is read in light of the Holocaust, something in which I don't feel qualified to do, it signifies in a different manner. The text resonates of hope, but one now is in a position to question such hope. The text signifies while at the same time resists any signification.

Metalepsis is the term that names how the second reading rears its head in the first, and the second and the first in the third. It is a term that speaks of intertextuality, that no text is an island unto itself, but always refers to other texts. Isaiah 43.10 as a trope elicits the whole context of Isaiah 40-55, not to mention all of 43, and transforms the source text as well as the final text. So what does a text that calls

Metalepsis is the term that names how the second reading rears its head in the first, and the second and the first in the third. It is a term that speaks of intertextuality, that no text is an island unto itself, but always refers to other texts. Isaiah 43.10 as a trope elicits the whole context of Isaiah 40-55, not to mention all of 43, and transforms the source text as well as the final text. So what does a text that calls

No comments:

Post a Comment